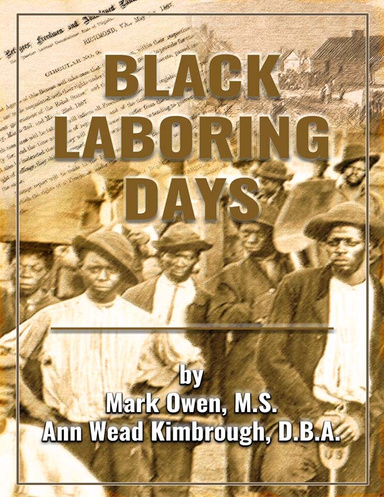

It’s’ Labor Day. The “celebration” is a U.S. holiday and has been dubbed the unofficial closing of summer. There are many layers to the meaning of Labor Day for Black folk. Here is an excerpt from the ebook, “Black Laboring Days,” Copyright © 2021 by Ann Wead Kimbrough, Mark Owen

Chapter Four

Labor Day and Black Codes, Black Laws

Most of us regard the Labor Day weekend each September

as the official end of summer. Yet, Labor Day had different

meanings for the once enslaved African Americans who

worked for no wages on lucrative agricultural plantations.

Even after the Union defeated the Confederate states in the

Civil War, those freed by the federal statute continued to

endure harsh conditions during the Reconstruction period.

Those conditions were imposed upon African Americans by

the Southern states’ Black Codes (read in the next section of

this blog) while U.S. labor unions were waging efforts for

the federal government to enact a national holiday in honor

of other laborers.

The federal law creating Labor Day was born to

recognize the employed men, women, and children. During

the Industrial Revolution in late 1800, several atrocities were

reported about the working conditions for the impoverished

and new migrants whose average workdays were 12 hours

and children as young as five were included. (Labor Day

2021: Facts, Meaning & Founding – HISTORY). On Sept. 5,

1882, the first Labor Day parade took place in New York

City. See below.

Black Codes, Black Laws

Meanwhile, African Americans were suffering as

laborers during the same late 19th century period. African

Americans’ treatment in the Industrial Revolution era was

deemed as carryover treatment from the days of mass

enslavement. Post-slavery and during the Reconstruction,

every Southern state’s legislature enacted Black Codes to

“protect their investments” (Project MUSE – Blue Laws and

Black Codes (jhu.edu) and to build infrastructure. In

Virginia, prison labor on the chain gang was primarily

comprised mainly of African Americans who were deemed

vagrants and guilty of other crimes under the state’s Black

Codes. The chain gang members were not compensated, and

their purpose was to build roads “to bring Virginia into the

automobile age.” (Project MUSE – Blue Laws and Black

Codes (jhu.edu)

Black codes required freed African Americans to sign

yearly labor contracts. If they refused to sign the agreements,

the laborer risked being arrested, fined, and forced to join the

chain gang and not receive any wages for their toils. (

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/black-codes)

https://nomoreslaveryyay.weebly.com/rights-and-vagrancylaws.html

According to numerous historical documents, Congress

passed legislation to repeal all Black Codes, yet the Southern

States continued with its practices.

(https://nomoreslaveryyay.weebly.com/rights-and-vagrancylaws.html)

There was an overlap of Black Codes in non-Southern states.

Known as the Black Laws, the restrictions were enacted in

conditions that included Ohio in 1803. Author Stephen

Middleton, (The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in

Early Ohio · Ohio University Press / Swallow Press

(ohioswallow.com) explains Black slaves and free African

Americans found refuge in Ohio. Yet, new laws prohibited

many movements and imposed restrictions that were

eventually overturned in 1886.

Real Labor Days

The real labor days began in the 17th century in the United

States. Enslaved ancestors from the Trans-Atlantic Slave

Trade were often sold and repurchased again at marketplaces

like this one on Whitehall Street in Atlanta, Georgia.

Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress,

Prints and Photographs Division

The involuntary work performed by slaves has been

documented in multiple media formats. However, leading

scholars on the topic of African Americans’ slave history,

“Clearly, dominant narratives at historic plantation sites have

long been maintained by a white elite class at the expense of

the enslaved and African American history in general. There

is evidence of inclusion of the enslaved at the plantation

museums; however, this movement is slow and

evolutionary—not revolutionary.” (SEGEOGLOGO.eps

(d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

The enslaved life was anything but glamorous. Southern

plantations were booming in commerce. Due to demands for

cotton, tobacco, rice, and all agricultural products, the wealth

of its owners increased the intensity to grow the slave

population. Dark-skinned people, including Spence Johnson,

the once free member of the Choctaw Nation, were placed in

involuntary servitude. He and his family lived in the Indian

Territory in 1850 when his mother and Johnson were sold at

a Louisiana slave auction. They were not brought to the

United States during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, yet

were stolen and sold to perform free labor on giant

plantations:

As if laborious tasks were not enough to complete, slaves

were the victims of horrific crimes against their bodies.

Sometimes the chopping off of legs and arms and even

women’s breasts were designed to keep slaves from fleeing

their plantations. In the case of the phenomenal inventor and

scholar George Washington Carver, he was castrated as a

child by his master. His enslaver wanted to ensure the

African American slave would not be intimate with the

White man’s daughter.

(George Washington Carver Was Not

Gay, But Castrated (Updated 2021) – MICHEAUX

PUBLISHING (wordpress.com

September Laboring Day

Ebook | By Ann Wead Kimbrough, Mark S. Owen

ISBN: 9781716435287